ADHD Resource Guide

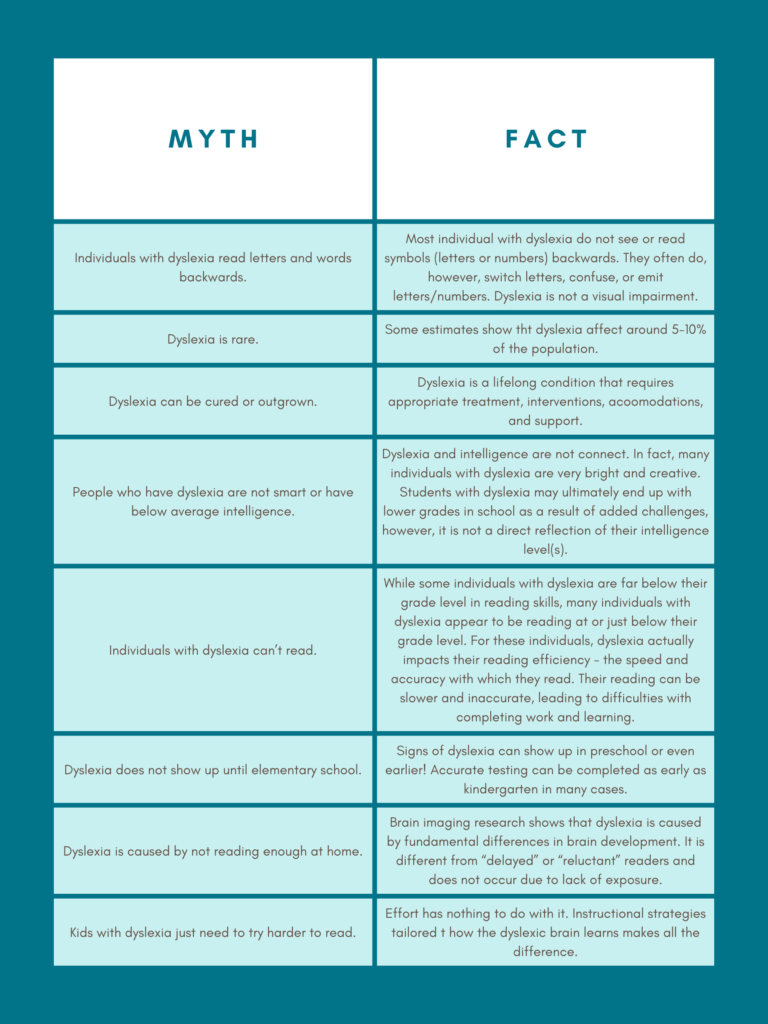

Despite being one of the most common learning disorders, dyslexia is frequently surrounded by misconceptions and myths that can lead to stigmatization and hinder effective treatment. Our goal is to debunk some of the most common myths about dyslexia and replace them with facts. We hope to provide accurate information that can help individuals with dyslexia, their families, educators, and the general public better understand this condition. From the myth that dyslexia is simply about reversing letters, to the misconception that people with dyslexia have below average intelligence, we will tackle these falsehoods head-on. So, without further ado, let’s dive in and separate fact from fiction!

Dyslexia is a neurodevelopmental disorder that impacts brain processes responsible for reading. Dyslexia impacts how the brain processes symbolic information, such as letters and numbers, associates these symbols with meaning (such as sounds and amounts), and the speed and accuracy with which the brain processes this information.

Dyslexia is a condition that is widely misunderstood. It is a neurological condition that affects the way the brain processes written and verbal language. Individuals with dyslexia are just as capable as their peers, however, they may require additional support, treatment, and resources to help them learn and be successful.

Having an understanding and awareness is key to eliminating the stigma associated with dyslexia or any other mental health condition. It’s our hope that we can collectively continue to educate ourselves and others about this condition, and foster an environment of acceptance and support for all learners.

We hope this post challenges you to look beyond the myths of dyslexia and perhaps even other conditions!

Click HERE to schedule an appointment

Read more about our testing services HERE

In the spirit of ADHD awareness month, let’s bust some of the myths out there and provide some accurate and potentially new, insightful information about ADHD.

First of all, what is ADHD? We hear about it all the time because it’s become pretty common in mainstream lingo, but what exactly does it mean? And why does it make sense to have a conversation about sensory seeking behaviors with ADHD?

In general, ADHD, or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, is not just about hyperactivity or inattention. It’s actually all about difficulties regulating arousal, attention/concentration, impulse control, as well as other executive functions that guide organized, goal-oriented behavior. A person with ADHD may find it extremely difficult to focus and sustain their attention, sit still, keep track of their belongings, categorize and organize things, plan and execute larger tasks, and control impulsive urges and behaviors. For example, have you ever known someone who just can’t seem to keep track of their car keys? Or a child who struggles to remember to bring home their homework? Or maybe you know someone that no matter how hard they try, they just can’t seem to keep their room picked up. How about someone that seems to really take a deep dive into the things they enjoy, but can’t find the motivation to plan or do things that are less important to them? All of these behaviors are normal on their own, but when observed in combination with other ADHD symptoms, and to a degree that they are impairing functioning at work, home or school… that person might have ADHD!

In addition to the symptoms and behaviors mentioned above, ADHD and many other neurodevelopmental disorders can also cause sensory seeking behaviors.

Have you ever seen a child climbing all over or jumping off of furniture, stomping their feet, purposefully falling, bumping into things or bouncing around? Have you ever seen a child or adolescent or maybe even an adult chew on their shirt or sweatshirt strings? Have you ever seen a child watch tv or their iPad while upside down? Or maybe they did a lot of spinning around or swinging? Have you ever seen a child watch tv or their iPad really loud? Or make loud, sort of strange repetitive noises? Maybe yelling or screaming? Any of these behaviors at first glance may have seemed like this child was “acting out” or “misbehaving”. But let’s look at this from another lens.

If you answered yes to any of these, you may have seen kids engage in sensory seeking behaviors! Sensory seeking behaviors help individuals regulate (increase or sometimes decrease) the stimulation their brain is getting. And more often than not, these behaviors are missed, overlooked, or misinterpreted as “bad behavior or bad parenting”. They are not “bad behavior”, nor are they a result of “bad parenting”. These behaviors are really important signals to parents, teachers, and clinicians about an individual’s need for sensory INPUT, not OUTPUT. And if these sensory needs are not met, it typically leads to an increase in needs and an increase and frequency and intensity of these behaviors. Meaning, ADHD behavior gets more disruptive sometimes because the individual is trying to regulate but isn’t getting what they need.

Understanding the relationship between ADHD and sensory seeking is crucial for developing effective strategies to manage these behaviors. By recognizing these connections, parents, teachers, and mental health professionals can better support children and adolescents with ADHD who exhibit sensory-seeking tendencies.

There are five main types of sensory seeking behaviors:

1. Oral Motor input

Examples: chewing, snacking, sucking, licking

2. Tactile input

Examples: finger tapping, using handheld fidgets, sensitivity to clothing, always using a specific blanket

3. Proprioceptive input

Examples: using the entire body- crashing into things, bouncing, climbing walls, jumping, stomping

4. Vestibular input

Examples: being upside down, swinging, spinning

5. Auditory input

Examples: watching tv or listening to music very loud, making repetitive noises, yelling or screaming

Now What?

So you’ve noticed your child engaging in sensory seeking behaviors, the question then becomes “now what”?

As a clinician, when I notice that a child is exhibiting sensory seeking tendencies, I make recommendations to clarify what needs the child has that are being expressed by these behaviors, including ensuring their diagnosis is clear and correct, and then I provide additional treatment recommendations. These recommendations may include getting in contact with the pediatrician/primary care physician, a possible referral to a neurologist, additional testing/assessments for diagnosis clarification, getting a referral for occupational therapy and/or physical therapy, and any other relevant additional services. In therapy we then work to increase the parent’s and child’s awareness of these behaviors, learn what need they are signaling, and learn to engage in positive, proactive coping and regulation. We practice these coping and regulation strategies so sensory seeking behaviors are less disruptive at home, school and work.

What do the parents do?

Parents should first and foremost understand that they have done nothing wrong and they have already done something invaluable and very important for their child by getting them help and support. Then parents can work with their provider to track these sensory seeking behaviors by asking, “what is this behavior telling us my child needs?” By tracking and understanding sensory seeking through this lens, your clinician can help you make a plan to meet your child’s needs at home and at school.

Having a child with ADHD and sensory needs is not easy, but the help and support is out there! We are here for you and we are here to make things easier for you and your child. They don’t have to go through life struggling and neither do you. It can get easier and it will.

ADHD and sensory-seeking behaviors often intersect, leading to added challenges in social interactions and classroom settings. However, with the right support, treatment, and accommodations, these sensory needs can be effectively managed. This not only helps the child navigate their daily life more comfortably but also fosters an environment conducive to their growth and development.

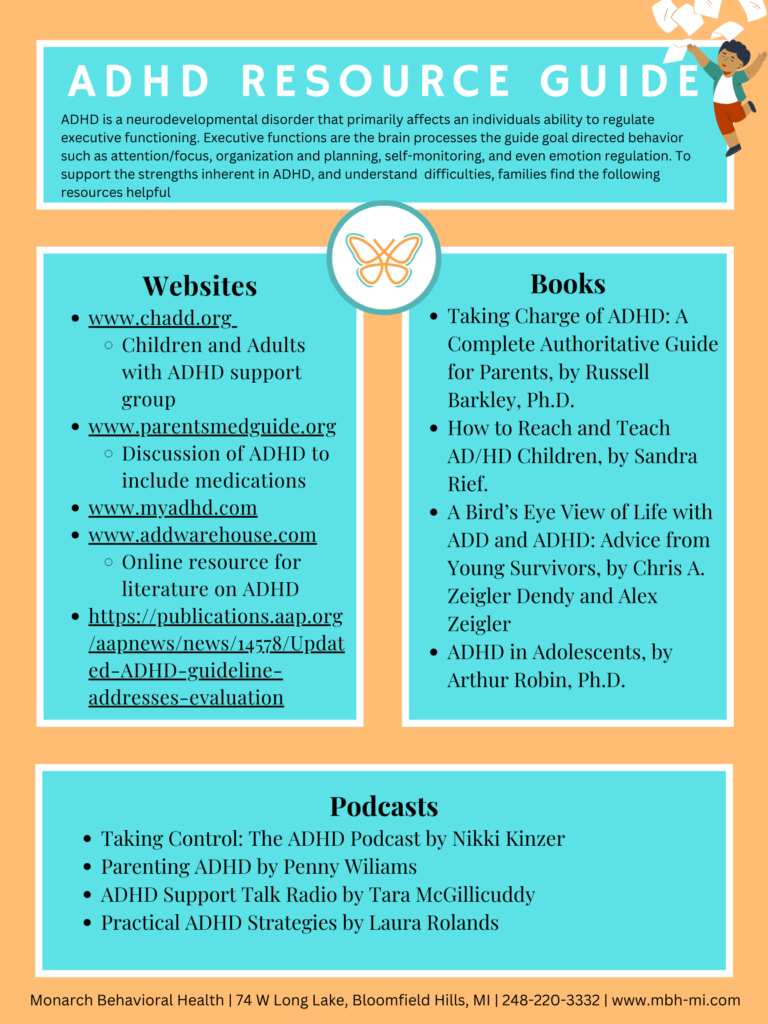

We have created a custom list of our favorite resources for more information about ADHD including websites, books, and podcasts. Please see our guide below and bookmark this page so you can refer back to it anytime!

links:

www.chadd.org – Children and Adults with ADHD Support Group

www.parentsmedguide.org – Discussion of ADHD to include medications

www.myadhd.com – Online resource for literature about ADHD

www.addwarehouse.com – Online resource for literature about ADHD

Updated ADHD guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics

Taking Control: The ADHD Podcast by Nikki Kinzer

Parenting ADHD Podcast by Penny Williams

Practical ADHD Strategies Podcast by Laura Rolands

*Monarch Behavioral Health is not affiliated with any of the abovementioned resources

Some people may think that ADHD is just a set of habits or a quirky personality type, but the truth is far more in-depth and interesting ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder that first appears in childhood and continues to affect individuals throughout adulthood. The label neurodevelopmental means that ADHD stems from differences in brain development. These differences in brain development result in difficulties with emotional and behavioral control as well as the brain processes responsible for planning, organizing, and executing tasks. Of course, most people have difficulties with inattention, overactivity, or impulsiveness at times. What distinguishes individuals with ADHD from those without the disorder, is the far greater frequency and severity with which these behavioral and emotional patterns occur, and the far greater impairment these difficulties cause in many areas of life, such as school, home, work, and relationships. ADHD is primarily a disorder of the cognitive abilities needed for self-regulation. These cognitive, or mental abilities are called executive functions and are the fundamental brain processes responsible for organizing goal driven behavior and inhibiting impulses. Individuals with ADHD struggle to remember what needs to be done, make a plan, conceptualize and manage time, remember and follow constraints and rules, identify ways to overcome obstacles, and experience extreme variability in their responses to situations. They also struggle to switch between tasks or situations, inhibit off task or ineffective behavior, and modulate emotional responding. Getting an accurate diagnosis of ADHD can be tricky because several other disorders have overlapping behavioral and emotional symptoms. Because of this, it’s important to understand how we know ADHD is a real disorder, and how we go about making an accurate diagnosis.

Many people ask, how do you know ADHD is a real disorder? How do you know these difficulties aren’t just ‘bad’ behavior, ‘bad’ habits, or a ‘difficult’ personality? To answer this, we turn to the last several decades of brain research on ADHD. Research clearly and repeatedly indicates that the ADHD brain is developing differently from the non-ADHD brain. When we look at groups of hundreds or even thousands of ADHD brains compared to non-ADHD brains, the differences in brain development between the groups are very clear. This profile of brain development differences is distinct and does not mirror any other disorder or injury. It is incredibly important to dispel any ideas that ADHD is due to an individual simply not trying hard enough or poor behavioral management. Instead, individuals with ADHD, and parents raising kids with ADHD, are often the hardest working people in the room! So why can’t we diagnose ADHD with brain imaging like a CAT scan or MRI? The truth is, ADHD affects several areas and functions of the brain and is a disorder with a wide range of symptoms and presentations. Although we can tell the difference between groups of brains very clearly, when just looking at one individual’s brain imaging results, the information just isn’t enough to ‘see’ ADHD clearly. This is actually the case for many medical disorders and diagnoses that originate or involve the brain. Many disorders can not be detected by brain imaging alone and require further testing, often by a psychologist or medical professional. To diagnose ADHD we use a battery of tests that assess these specific areas of brain functioning, and also rule out all other disorders that have common symptoms with ADHD, such as anxiety disorders and learning disorders. This type of assessment, a neuropsychological assessment, is an accurate way to diagnose ADHD in both children and adults.

Research suggests that ADHD is a result of one or more issues that affect brain development. In the majority of cases, ADHD brain differences are due to genetics; inherited from parents. In recent years, specific genes and gene mutations have even been identified as likely causing or contributing significantly to ADHD. However, in a minority of cases, brain development delays are due to subtle brain injuries or exposure to substances or toxins that occurs during gestation, birth, or early childhood. We also know that getting the correct treatment helps brain areas affected by ADHD to develop further.

We know ADHD is a real disorder and that ADHD brains are developing differently, but in what ways? The brains of individuals with ADHD have structural and functional differences, as well as differences in brain chemistry when compared to typically developing brains.

Studies using an electroencephalograph (EEG), which measures brain activity, indicate that the electrical activity in brains of children with ADHD is lower than that of typically developing children. Specifically, children with ADHD have an increased amount of slow-wave brain activity which is often associated with immaturity of the brain, drowsiness, and lack of concentration. Children with ADHD have also been found to have less blood flow to the frontal area and in the caudate nucleus, which is important in inhibiting behavior and sustaining attention. Now, you might be wondering how is it that children with ADHD, who appear more active and energetic than children without ADHD, could have brains that are less active? The areas of the brain that are less active in those with ADHD are those areas that are responsible for inhibiting behaviors, delaying responding to situations, and permitting us to think about our potential actions and consequences before we respond. The less active these centers are, the less self-control and self-regulation an individual will be able to demonstrate. Thus, these areas of underactivity result in more difficulty regulating emotional and behavioral responding.

Neurotransmitters are the chemical messengers in the brain that help transmit information from one nerve cell to another. Individuals with ADHD appear to have less of these messengers, or cells in the brain are less sensitive to them. Specifically, evidence seems to point to a problem in how much dopamine (and possibly norepinephrine) is produced and released in the brains of those with ADHD. Therefor, stimulant and non-stimulant medications, used to treat ADHD, work to make more of these chemical messengers available. This helps with communication between brain centers and structures and produces significant improvements in behavioral and emotional regulation of those with ADHD.

Individuals with ADHD posses a great many strengths such as creativity, ability to hyper-focus on tasks and areas of great interest, and less traditional problem-solving approaches. Evidence-based treatment for ADHD often includes medication prescribed by a medical practitioner, as well as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and parent support. Those uncomfortable with medication often engage in CBT alone and experience a great deal of improvement. While CBT helps the individual develop coping strategies and effective patterns of thinking and behaving, treatment also focuses on building personal strengths and positive identity. Although ADHD is a lifelong neurodevelopmental disorder, and symptoms generally persist into adulthood, we do know that children who are treated with medication and therapy (specifically cognitive behavioral therapy with parent support) have the best outcomes in adulthood. Medications and evidence-based therapy appear to improve brain volume and connectivity over time, implying that engaging in treatment may actually help the brain maturation process. The interaction of increased learning opportunities due to proper treatment also has a positive impact on brain growth and connectivity. As an individual with ADHD obtains treatment, they are actually changing their brain! Treatment for pediatric ADHD should also include a parent component. Parenting support focuses on developing parenting practices and strategies, as well as household structure that support the functioning and growth of a child with ADHD. Kids with ADHD often do not respond to typical parenting strategies and need more ADHD specific support. And finally, treatment for ADHD also involves receiving support and accommodation in the school and/or work environment. Those with ADHD can flourish when they are working simultaneously to use effective coping and capitalize on their strengths.

Many kids and teens need Individualized Education Plans (IEP) to support their development and education. The IEP process can be an overwhelming and confusing path to navigate as a parent. We want to help make you feel prepared and informed about the process. The following steps are what will typically occur through the IEP process.

If you, as a parent, are concerned your child may be having learning struggles, social, emotional or behavioral difficulties that are interfering with learning, developmental delay, or any disability that is impacting their education needs you can begin the IEP process. The process begins with a formal request to receive comprehensive evaluation for special education eligibility. This evaluation assesses if your child qualifies for special education services. Each child with an IEP must be shown to qualify for services under one of several categories. This request can be verbal or written; although we recommend a written request for documentation purposes. The Michigan Alliance for Families has sample request letters available for parents to feel prepared without the hassle. We’ve included the link below for your convenience. It’s important to keep a dated copy of this request yourself for records. Someone within the school system who has concerns about your child’s learning or development can also make a request for an evaluation. You will be notified if this happens. Sometimes schools will gather data and/or put informal interventions into place before a child is formally referred for an IEP evaluation.

After a formal request has been submitted to the school they have 10 calendar days to respond. The school will either deny the request, stating the reasons why, or agree to conduct the evaluation. A (usually brief) meeting will then be held with parents to review the evaluation process and obtain written consent before the evaluation is conducted.

After the request has been made and accepted, the school assembles a Multidisciplinary Evaluation Team (MET) of professionals to evaluate your child. This team may include general education teachers, special education teachers, psychologists, social workers, therapists, or other specialists. This team engages in the Review of Existing Evaluation Data (REED) to determine what data they have regarding the areas of concern, as well as what additional evaluations must be completed. The team will develop a written report with recommendations for eligibility.

Evaluations are often requested because parents and/or teachers notice a child is struggling a great deal academically, socially, emotionally/behaviorally or developmentally, but they don’t know exactly why. It is important to know that the school does not and can not diagnose your child with a learning disability such as Dyslexia or Dysgraphia, language disorder, or neurodevelopmental disorder such as ADHD, Autism Spectrum Disorder, or Developmental Delay. These diagnoses can only be made by qualified professionals outside the school context. A diagnosis can support the case for eligibility in many cases.

Evaluations may be conducted during this time that look at academic functioning, behavioral/emotional functioning, executive functioning, and socio-emotional functioning within the classroom. You can also ask that private professionals, such as your psychologist or counselor are invited to be part of the MET and attend this meeting. The data from the evaluation guides what supports, accommodations and interventions your child may receive. If your child has a disability that has already been identified and documented by a professional (e.g.,. psychologist, medical doctor, speech pathologist, or occupational therapist) this process can be pretty straightforward.

Diagnoses having to do with learning (e.g., Dyslexia, Dysgraphia, Dyscalculia), socio-emotional or behavioral functioning, neurodevelopment (e.g., ADHD), or developmental delay are generally made by psychologists who work at an outpatient clinic or hospital setting, outside of the school. These diagnoses are typically made after a full psycho-educational or neuropsychological evaluation has been completed. Head over to the psychological assessment/testing page of our website if you would like to learn more about this type of evaluation (https://www.mbh-mi.com/testing/general-information/). You may share the psychologist’s report with the school to help them understand your child’s difficulties and diagnoses. Schools generally use the evaluation data in psychologists’ reports, as well as the recommendations given to help support and structure the IEP.

A second meeting within 30 school days will be scheduled with the IEP Team to discuss the results of any additional evaluation and your child’s eligibility for special education services. The IEP team includes parents, general education teachers, special education teachers, psychologists, counselors, and a representative from the school. This can be an overwhelming process and meeting for parents, and many parents choose to bring a child advocate to the meeting. This advocate should have a working knowledge of IEP procedures, law, and most importantly, your child. At Monarch Behavioral Health, we frequently attend these meetings with parents. We aim to advocate for evidence-based interventions for children, support parents, forge a partnership with teachers and school staff, and explain psycho-educational or neuro-psychological testing results and diagnoses.

Once eligibility has been established, the IEP Team will put together an initial IEP. This may or may not already be developed at this meeting. If it is not, parents will receive notification when the IEP is complete and when it will be implemented. Parents will have the opportunity to review the IEP with the IEP Team and get an understanding how the school will be supporting their child’s needs. If you want, after the meeting is over you should be able to take the IEP document to review it at home. Be sure to ask any questions you may have. Once parents sign the IEP and consent, the school will begin implementing the IEP within 15 school days.

Progress monitoring is used to assess your child’s academic, behavioral, executive functioning, and socio-emotional functioning on IEP goals and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions and instruction as the year progresses. Progress monitoring tells the teacher what a child has learned and what still needs to be taught. Monitoring should determine your child’s current level of performance, measure your child’s performance on a regular basis, and compare the expected progress to their actual performance. We encourage actual data to be collected for monitoring, as opposed to teachers and staff’s general impressions. During this step the IEP team will consider changes to instruction or services when your child’s progress toward goals is not being made, process is slower than expected, or the goals have been met. There is no set timeline for progress monitoring. We often suggest progress monitoring be done monthly for new IEPs, and quarterly for ongoing IEPs.

You should meet with the IEP team at least every 12 months for an annual review. Annual reviews often take place in the spring, as the school year is drawing to a close. At this time, the team will examine your child’s progress towards goals and make appropriate updates as they develop. It is recommended parents ask about the specific measurement of these goals. A parent or school team member may request an IEP review prior to the annual 12 month meeting if the need arises.

Every three years, the IEP team will do a formal re-evaluation to document a student’s changing needs and consider progress on goals. Reevaluation will look similar to the initial evaluation. It begins with a Review of Existing Evaluation Data (REED) available for the child, and may include the child’s classroom work, discipline records, performance on State or district assessments, and information provided by the parents. If needed, the school may conduct an updated evaluation on academic, behavioral, executive functioning, and socio-emotional functioning. Parents often seek an updated psycho-educational or neuropsychological assessment from a professional outside the school at this time to support and add to the REED. Similar to the initial IEP meeting, parents will sit down with the team and come up with a revamped IEP, setting new goals and delineating new services, supports and accommodations. Again, parents often choose to invite a child advocate to this meeting.

We encourage all data and interventions to be formally documented. When changes in interventions and approaches occur, amendments can be made to the IEP. Although we appreciate all the informal strategies and approaches teachers and school staff take to address a kid’s needs, when these strategies and approaches are not documented, we lose an account of what worked and what didn’t. An important purpose of the IEP is to create a road map. This road map serves the child now, as well as in the future years. We encourage parents to keep all their child’s IEP documents and evaluation data. Keeping these documents organized can help you feel better prepared for meetings and stay up to date on your child’s progress. Reviewing these documents also often gives helpful ideas and support for interventions down the road.

GREAT TIP!

Making an IEP binder is a great way to keep information organized and at the ready when you need it. This tool can help you communicate and collaborate with teachers and your child’s IEP team. The binder can include communication logs where you keep track of meetings, phone calls, letters, emails, and other important interactions with the school. It is important to keep track of evaluations, evaluation reports, standardized and state testing data, and your consent forms. It’s also a good idea to have copies of the IEP handy since they need to be updated annually. You’ll be able to look at the exact changes made at IEP updates, as well as when services started or ended. Report cards and progress notes can help you monitor your child’s progress toward each annual goal in the IEP. Sample work can be included that shows signs of progress or concerns. Lastly, keep a copy (if included) of your child’s behavior intervention plan or contract to see how your child is progressing in the classroom.

Even though all school districts will have slightly different procedures in place, always ask when the following steps are not conducted. The steps include; 1) Referral, 2) Parent Notification, MET & REED, Additional Evaluation, 3) Individualized Educational Planning Meeting, 4) IEP Implementation with Progress Monitoring, 5) Annual Review, and 6) Re-evaluation.

We know the IEP process can be daunting to navigate as parents. Don’t hesitate to reach out for support and consultation. At Monarch Behavioral Health we work closely with families, school staff, and administration to advocate, create, and implement individualized school accommodations that work for your child.

If your family needs additional support and guidance through the IEP process and want to gather more information for empowerment look at the following websites listed below.

Michigan Alliance for Families is a statewide resource that connects families of children with disabilities to resources to help improve their children’s education. They assist in facilitating parent involvement as a means of improving educational services and outcomes for students with disabilities. This resource assists you in knowing your rights, how to effectively communicate your child’s needs, and advises on how to help your child develop, learn, and thrive in the school context.

https://www.michiganallianceforfamilies.org

The Student Advocacy Center of Michigan is another statewide resource that supports families in knowing their rights by understanding policies, laws, and processes. They provide free templates for building letters needed throughout the IEP process. Bonus! They also provide a Statewide Helpline for general education and special education students to receive free support and education advocacy advice every step of the way.

https://www.studentadvocacycenter.org

Disability Rights of Michigan is a federally mandated protect and advocacy system for Michigan. A wonderful resource manual they provide families with is the “Students with Disabilities: An Advocate’s Guide”. Each chapter includes a brief summary, a list of “Advocacy Hints,” detailed descriptions of state and federal rights, sample letters, and resources for more information.

https://www.drmich.org/resources/special-education/

Recent Comments